chilblain

A blain or sore produced by cold; a tumor affecting the hands and feet, accompanied with inflammation, pain, and sometimes ulceration. — Webster, 1882

To cure chilblains slice raw potatoes, with the skins on, and sprinkle over them a little salt, and, as soon as the liquid therefrom settles in the bottom of the dish, wash with it the chilblains; one application is all that is necessary. – March 1881, Brookings County Press

To cure chilblains slice raw potatoes, with the skins on, and sprinkle over them a little salt, and, as soon as the liquid therefrom settles in the bottom of the dish, wash with it the chilblains; one application is all that is necessary. – March 1881, Brookings County Press

Although the word “chilblain” is only used once in the Little House books, during the writing of The Long Winter, there was some discussion between Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane about the word’s spelling and origin. In one of the Hard Winter manuscripts, Laura wrote to Rose, reminding her that she had asked about chillblains [sic] in the past and Laura had described them to her. Laura was unable to find the word in her dictionary, but she wondered if it was an old time word that should be spelled chillbanes, because it must mean that “the bane of my life is a chill.” Bane also meant to poison, so Laura wondered if the word meant chill poison. Later in the manuscript, she adds a second note, writing that the more she thought about it, the more certain she was that Ma used to pronounce the word as chillbanes and it was some careless way of their speaking that added the “l” to it. Laura then instructed Rose to spell the word “chill-b-a-n-e-s.”

Although the word “chilblain” is only used once in the Little House books, during the writing of The Long Winter, there was some discussion between Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane about the word’s spelling and origin. In one of the Hard Winter manuscripts, Laura wrote to Rose, reminding her that she had asked about chillblains [sic] in the past and Laura had described them to her. Laura was unable to find the word in her dictionary, but she wondered if it was an old time word that should be spelled chillbanes, because it must mean that “the bane of my life is a chill.” Bane also meant to poison, so Laura wondered if the word meant chill poison. Later in the manuscript, she adds a second note, writing that the more she thought about it, the more certain she was that Ma used to pronounce the word as chillbanes and it was some careless way of their speaking that added the “l” to it. Laura then instructed Rose to spell the word “chill-b-a-n-e-s.”

Laura was incorrect. The word is chilblain, according to Webster’s 1882 Dictionary, and it is a combination of the words chill (meaning cold) and blain (meaning inflammation). In use by the mid-1500s, by the early 1800s, it meant an “inflammatory swelling produced by exposure to cold, affecting the hands and feet, accompanied with heat and itching, and in severe cases leading to ulceration.” – O.E.D., 1889.

In published The Long Winter, while the Ingalls family waits during a blizzard to learn if Almanzo and Cap were successful in bringing wheat to feed the starving town, Wilder describes the miserable cold the family is enduring, with their “chapped, numb hands” and their “itching, burning chilblained feet.” Chilblains may occur on the hands or feet after prolonged exposure to cold temperatures. The cold causes blood vessels near the skin’s surface to constrict, and if the skin is then warmed quickly, the smaller vessels can’t handle the increased blood flow to them and blood flows into the surrounding tissue, causing redness, swelling, and itching. Poor circulation, continued exposure to cold and damp conditions, and a poor diet can make the condition worse. Chilblains can last for weeks, and some people seem to be afflicted with them more than others.

The best way to keep the feet free of chilblains is to protect them from continuous cold. Make sure shoes and socks are dry, and if possible, warm them before wearing. Avoid wearing tight boots, shoes, and socks/stockings. If your feet are cold at night, sleep in socks; Mary Ingalls’ woolen-blanket bedshoes helped keep her feet warm! Move around frequently rather than sitting in one place, and massage lotion into the feet to aid in circulation. If skin is cracked or bleeding, use an antibiotic ointment. Never warm the feet too quickly if chilled.

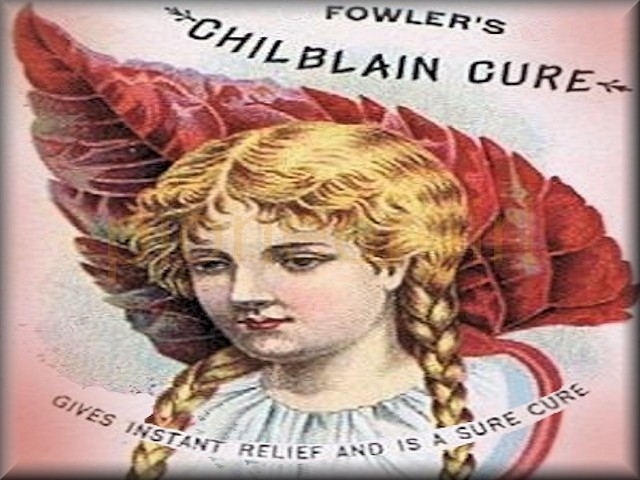

The following article from the 1880s gives the believed causes and proposed treatment of chilblains at the time of the Little House books:

Chilblains. Some women suffer terribly from chilblains, which are not only painful but when they appear on the hands cause great disfigurement. They are caused by frosted or congealed blood, which is difficult to disperse; consequently prevention is better than cure, with the following precautions to be taken immediately upon the beginning of cold and frosty weather.

Wear high, warm under bodices, and, above all, let your dress sleeves be warmly lines, and let the sleeves reach to the wrist. A pretty fancy cuff will help greatly, and flannel or swan’s-down sleeve linings are advisable. Wear woolen stockings, well drawn up by suspenders, as cold feet affect the whole body, especially the head and hands. At night put a teaspoonful of spirits of ammonia in the water, and use a flesh brush for five or ten minutes; then dry, and if you do not sleep in gloves, wear warm cuffs under your nightgown, and white woolen sleeping socks.

Never plunge the hands into very cold or very hot water, and do not expose them to the air without stout gloves and a warm muff. Above all, attend to the wrists and arms, as wrapping the hands only is of little avail. Long, close fitting armlets do more to prevent chilblains than any outward applications. If chilblains appear in spite of or from neglect of these precautions, let not the first twinge be neglected.

Prepare the following mixture, and apply night and morning, or whenever the chilblain is troublesome, and remember that friction, combined with a stimulating lotion, helps to disperse the chilblain: mix spirits or rosemary, five parts, to wine, one part. On the first sign of redness or irritation, an excellent plan is to rub briskly with the lotion named, and to cover the part with adhesive plaster; but friction is earnestly advised, or if this is neglected until there are symptoms of their appearance, then apply a lotion and friction every two hours. Broken or ulcerated chilblains should be washed with tincture of myrrh in water; but with care and wearing warm clothing chilblains may be prevented, or at least will not reach beyond the first and easily cured stage. — “Physiology And Hygiene. Rheumatism of the Joints and Other Affections That Come with Cold Weather,” in the Jackson (Michigan) Citizen Patriot, November 9, 1888, page 3.

chilblain (TLW 28)