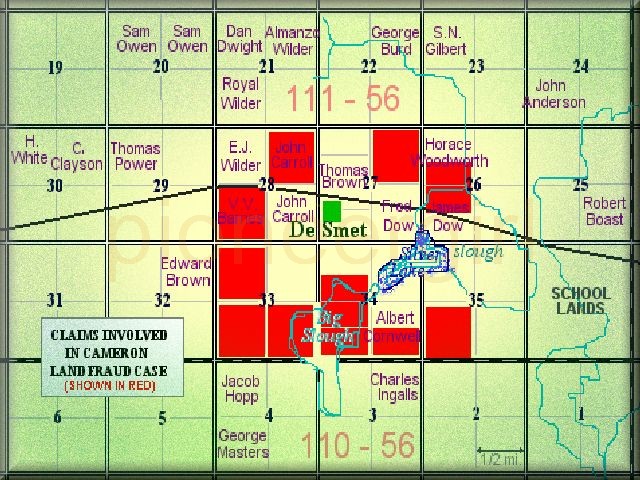

the Cameron gang

Men who were given or purchased claims around the townsite of De Smet that had been obtained fraudulently as part of a land scheme set up by John D. Cameron of Sioux Falls.

Fred Dow was the only man to get filed on land in the vicinity ahead of the Cameron filing that claimed the land of every townsite along the railroad. – De Smet News, June 1930.

Fred Dow was the only man to get filed on land in the vicinity ahead of the Cameron filing that claimed the land of every townsite along the railroad. – De Smet News, June 1930.

Anyone who has read the Little House books has heard of Robert Boast, Charles Ingalls, Jake Hopp, Eliza Jane Wilder, and Edward Brown. They all had claims within a two mile radius of De Smet.

Anyone who has read the Little House books has heard of Robert Boast, Charles Ingalls, Jake Hopp, Eliza Jane Wilder, and Edward Brown. They all had claims within a two mile radius of De Smet.

If you’ve studied Laura Ingalls Wilder’s historical Little Town on the Prairie, you know that Sam Owen, George Masters, Chauncey Clayson, and Silliman Gilbert also had claims near De Smet. You might recognize some of the other names on the map I’ve drawn. I didn’t include everybody, so just because there’s no name on a quarter section, it doesn’t necessarily follow that the land wasn’t occupied during the Little House years. It probably was.

Now, what about Charles Curtis, Newton Morse, Samuel Craig, Walter Sharp, and John Challice? They filed on claims in 1879 and 1880, almost all of which were within a mile of De Smet. They aren’t mentioned in the Little House books, and few people have ever even heard of them or know why they are important.

These men and a half dozen others were part of what became known in De Smet as the Cameron gang, a group of men who – through the land office at Mitchell, Dakota Territory – were given or purchased fraudulent land documents or counterfeit first filing papers for preemption claims.

The men’s names were probably also fake.

In 1879, Sioux Falls attorney and land agent John D. Cameron (that was his real name) set up a complicated scheme by which he would print, fill out, advertise, and file paperwork for claims surrounding townsites up and down the new railroad line in Dakota Territory. They were dated to appear that first papers had been filed in Mitchell before or near the dates other men filed on the same lands through the Watertown or Yankton Land Office in the fall of 1879 or early winter months of 1880. This would allow time for the required six months to go by before preemption was possible, and still be timed to beat the rush of settlers in the spring. Much of the land was obtained using fake scrip, whereby lands were given to former soldiers.

Only very rarely did any of these land fiends ever see the land they had papers for, much less live on it or improve it. And since only a few legitimate settlers spent the winter of 1879-1880 near some of the new railroad townsites (such as Walter Ogden and the Ingallses at Silver Lake), there was nobody around to dispute any claim that these men had done so. They “witnessed” each other’s claims, and nobody was the wiser.

Meanwhile, there were honest-to-goodness homesteaders — such as Visscher Barnes, Horace Woodworth, Almanzo Wilder, Charles Ingalls, and Robert Boast, among others — who had filed on claims but didn’t spend that first winter on them. They built rough shanties and left a few personal belongings in place to show that they had been there and would be back. In some cases, a few acres had been plowed. Most wintered back east, and they arrived with their loved ones as soon as they were able to get there in the spring of 1880, ready to settle down to some serious homesteading. Men worked on their claim shanties, built stables, dug wells, started plowing, and planted gardens.

The plan was that members of the Cameron gang would show up in De Smet or whatever town their “claim” was near, holding a patent or deed in hand, and find some claim jumper on THEIR land! They would show that they had filed proper papers and insist that they had spent the winter there. They had witnesses; just look. They hadn’t been gone long; they had only gone to fetch supplies. The land was THEIRS!

But then, rather than trying to throw the poor, scared homesteader and his family off the land, they would decide to be magnanimous and offer to relinquish the claim in exchange for filing fees or some reasonable relinquishment payment and they would just go elsewhere and take another claim. No problem; no harm done. In some cases, De Smet settlers were so scared that they paid what was asked. Rev. Horace Woodworth did. However, some men were intimidated into taking out loans from banks back east in order to buy the land outright for the preemption price, or even more. After all, they had picked the spot because of its proximity to the townsite, and they wanted to live there. The land was sure to only increase in valuable.

The Cameron gang didn’t reckon with De Smet attorney and Probate Judge, Visscher Vere Barnes. One of the members of the gang just happened to try to take over Lawyer Barnes’s homestead, and Barnes sought out and fought their ring-leader, John Cameron, for three years in court, traveling to the Department of the Interior and the General Land Office in Washington, D.C. Barnes took the case to the Dakota Territory Supreme Court.

And won.

And look who testified in the case (Senate documents, 1882-1883):

Cameron gang