hatchet

A small ax with a short handle, to be used with one hand. — Webster, 1882

Carry A. Nation was greeted by a full house on her visit to De Smet last week Thursday night… A large number of miniature hatchets were sold and are being worn by young and old. — De Smet News, January 21, 1910

Carry A. Nation was greeted by a full house on her visit to De Smet last week Thursday night… A large number of miniature hatchets were sold and are being worn by young and old. — De Smet News, January 21, 1910

A hatchet or ax (or axe, the English spelling) consists essentially of a broad heavy type of chisel, called the head, having an eye running in the direction of the cutting edge for receiving a handle, so that, like a pick in one particular, it is suitable for giving out a blow, to be expended in actuating the cutting edge, which forms a part of the tool itself; the main difference being that a pick is used for cutting rock, but an axe for cutting tember. The back of the blade is called the poll, and can be made to form a surface for striking moderate hammering blows.

A hatchet or ax (or axe, the English spelling) consists essentially of a broad heavy type of chisel, called the head, having an eye running in the direction of the cutting edge for receiving a handle, so that, like a pick in one particular, it is suitable for giving out a blow, to be expended in actuating the cutting edge, which forms a part of the tool itself; the main difference being that a pick is used for cutting rock, but an axe for cutting tember. The back of the blade is called the poll, and can be made to form a surface for striking moderate hammering blows.

The hatchet and axe are almost identical in character. Some people consider the axe is the heavier tool, with heads weighing above three pounds, and suitable for use with both hands, while the hatchet is intended to be used by one hand only, and has a head weighing under three pounds. The hatchet in the photograph is a broad hatchet, as advertised second from left, below.

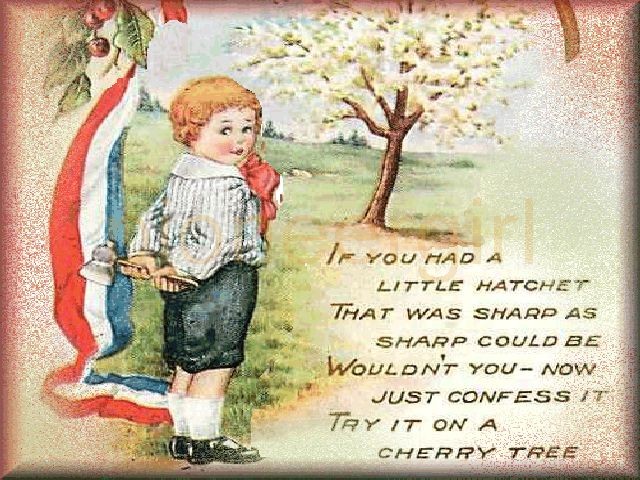

“Father, I cannot tell a lie. I did it with my little hatchet.” In Little Town on the Prairie (Chapter 19, “The Whirl of Gaiety”), one of the “wax figures” at the “Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks” Friday night literary was said to represent George Washington, making chopping motions with a hatchet. This, of course, is in reference to the mythical story that George Washington, as a boy, cut down a cherry tree, and when acused of the deed he replied, in effect: “Father, I cannot tell a lie; I did it with my little hatchet.” The hatchet, therefore, has long been regarded as a humorous symbol of Washington’s truthfulness.

The myth may have originated with later editions of History of the Life and Death, Virtued and Exploits of General George Washington, written by Mason Lock Weems and first published in 1800. Also known as “Parson Weems,” the author penned a book filled with half-truths and fanciful stories intended to paint Washington as a folk hero. The story from the 1809 edition reads:

thor penned a book filled with half-truths and fanciful stories intended to paint Washington as a folk hero. The story from the 1809 edition reads:

When George… was about six years old, he was made the wealthy master of a hatchet! of which, like most little boys, he was immoderately fond, and was constantly going about chopping everything that came in his way. One day, in the garden, where he often amused himself hacking his mother’s pea-sticks, he unluckily tried the edge of his hatchet on the body of a beautiful young English cherry-tree, which he barked so terribly, that I don’t believe the tree ever got the better of it. The next morning the old gentleman, finding out what had befallen his tree, which, by the by, was a great favourite, came into the house; and with much warmth asked for the mischevous author, declaring at the same time, that he would not have taken five guineas for his tree. Nobody could tell him anything about it. Presently George and his hatchen made their appearance. “George,” said his father, “do you know who killed that beautiful little cherry tree yonder in the garden?” This was a tough question; and George staggered under it for a moment; but quickly recovered himself and: looking at his father, with the sweet face of youth brightened with the inexpressible charm of all-conquering truth, he bravely cried out, “I can’t tell a lie, Pa; you know I can’t tell a lie. I did cut it with my hatchet.” — “Run to my arms, you dearest boy,” cried his father in transports, “run to my arms; glad am I, George, that you killed my tree; for you ahve paid me for it a thousand fold. Such an act of heroism in my son is more than a thousand trees, though blossomed with silver, and their fruits of gold.” — Mason Locke Weems, A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits of General George Washington: With Curious Anecdotes, Equally Honourable to Himself and Exemplary to His Young Countrymen (New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1918) , 22-23.

The 1918 Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York include cite another source for this myth. In this volume, it was reported that Augustine Washington’s journal had been found, and the entry for March 1, 1739, reads:

A fine day and warm. This A.M. I found my best young plum tree spoiled with a saw. I thought it was a vagabond, spoke of it at noon. My son George owned the deed. First I was vexed and minded to whip him, but did not. He was truthful and repentant. He cut it with a small handsaw.

Do you believe either story? If the moral of the George Washington story is “Always tell the truth,” then perhaps the moral in the examples above is, “Don’t believe everything you read in print.”

hatchet (BW 3, 7; FB 7, 18, 20; LHP 4-5, 11; BPC 21; LTP 19; PG), see also ax, tomahawk