Dr. William H. York

Kansas doctor murdered by the Bloody Benders in March 1873.

A Real Bargain. An 80 acre farm, about seven miles south-west from Independence, known as the Dr. York farm, about 30 acres in cultivation, good land, pasture fenced, two good wells, a story and a half house, with cellar. Will be sold very low, part cash and balance on tie to suit, at 10 per cent. Inquire at the Tribune office, or address, J.H. York, Ft. Scott, Kansas. -South Kansas Tribune, June 6, 1883.

A Real Bargain. An 80 acre farm, about seven miles south-west from Independence, known as the Dr. York farm, about 30 acres in cultivation, good land, pasture fenced, two good wells, a story and a half house, with cellar. Will be sold very low, part cash and balance on tie to suit, at 10 per cent. Inquire at the Tribune office, or address, J.H. York, Ft. Scott, Kansas. -South Kansas Tribune, June 6, 1883.

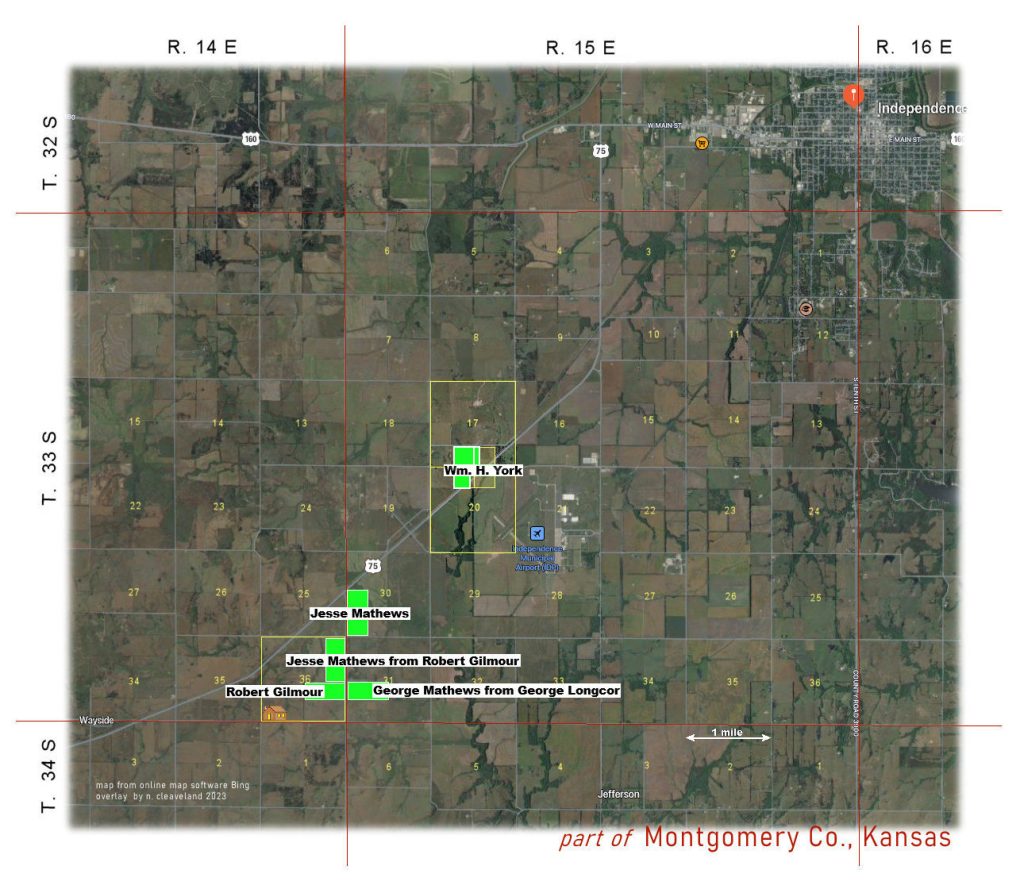

Map showing the location of Dr. York’s farm, all or part of the SE-SW & SW-SE 17 and the NW-NE & NE-NW 20, Township 33S, Range 15E of the 6th P.M., originally purchased by Benton Toal in July 1871. Longcor, Gilmour, and Mathews properties are marked. Although the Ingallses left Montgomery County prior to Dr. York’s murder, the Little House on the Prairie / Charles Ingalls cabin site is shown on the SW 36-33-14, and Charles Ingalls must have known both George Longcor and Robert Gilmour.

Whenever a new book about the Bloody Benders comes out or a discussion pops up, there are a few names mentioned in connection with Dr. William York as having been his neighbors: Robert Gilmour, George Longcor, and Jesse Mathews. As Gilmour and Longcor are known neighbors of the Ingalls family in Indian Territory, I wondered where Dr. York lived and if it was close to where the Little House on the Prairie Museum and replica cabin is today, even though William York and Jesse Mathews both moved to Montgomery County after the Ingallses had left.

Unlike the Ingallses, the Yorks weren’t living in Montgomery County when the 1870 census was taken; they moved to Kansas the following year. Like Charles Ingalls, Dr. York didn’t purchase land, so his name isn’t found in the places you’d traditionally look for early settlers: tract books, patent records, school land sales, and deeds. Newspaper articles from 1873 place the Yorks southwest of Independence near Onion Creek, and in her 1875 book written in memory of her husband, Mary York wrote that they came to the area in August 1871, but lived on an adjoining place until their house and stables were finished and wells and cellar dug, and that they moved into the house in February 1872. [p.10] Their home was “in a beautiful location, and just fitted up ready to begin beautifying it.” [p. 5] One of the things Dr. York did while visiting with his nursery-owning father at Fort Scott before heading home was to order shrubs and plants for the yard.” [p. 6] That doesn’t sound like something most renters would do, unless, perhaps, beautification was part of the rental agreement. [-Mary E. York, The Bender Tragedy. To the Memory of my Husband, Dr. W.H. York, Murdered in Labette Co., Kansas, March 1873 (Mankato: Geo. W. Neff Book and Job Printing, 1875).]

A decade after Dr. York was murdered, a notice advertising the “Dr. York farm” for sale appeared in the South Kansas Tribune. I’d already searched deeds for Mary & William York and found no purchases, so I looked for J.H. York sales after the June 1883 ad, and would then work my way back to 1873. The trouble is, there was also a much later newspaper bit indicating that Nathan High (1806-1895) “bought the Dr. York farm soon after the Bender tragedy.” [-The Evening Star (Independence, Kansas), September 26, 1902)] Would they turn out to be the same parcels?

One Julius York sale fit: July 3, 1883, J.H. York of Fort Scott sold 80 acres to William B. Seth, an Independence real estate agent in the partnership of Strahan, Seth & Co. It was an odd-shaped parcel: the SE-SW 17 & NE-NW 20, except a strip 20 rods wide off the east side of the NE-NW 20, also a strip 20 rods wide off the west side of the SW-SE 17, all in Township 33, Range 15. Montgomery County deeds also shows that on July 1871 – before William York was murdered, not afterwards – Nathan High purchased the SW-SE 17 and NW-NE 20-33-15. The J.H. York sale and Nathan High purchase had only ten acres in common; was this all there was to the York farm? To get a better understanding of the William York farm, it’s best to go back to the beginning.

To follow along with maps, see my comments to THIS POST on my pioneergirl Facebook page; it was posted on September 12, 2023.

R. Benton Toal (the BLM database has his name as Benton “Goal”) was in Independence Township for the 1870 census: R.B. (age 55), wife Elinor (48), and three children: Josie, George, and John. Toal purchased 160 acres on July 21, 1871: the SE-SW & SW-SE 17 and the NW-NE 20, selling it the same day in two parcels. The west half, he sold to Damon Cheney, a Massachusetts banker acting on the behalf of Senator Alexander York, Dr. York’s brother. The east half was sold to Nathan High of Shelbina, Missouri, which is where Dr. York and Senator York were enumerated on the 1870 census, as well as their parents, Margery & Miner York, who settled in Fort Scott. As the same arrangement was made between Alexander York and Damon Cheney for land that was transferred to his father in Bourbon County in the spring of 1874, it’s likely that title would have been transferred to Dr. York for at least the west half of the Toal quarter section, had Dr. York not been killed.

In August 1873, Damon Cheney sold the western parcel, except for a 10-acre strip of land on the east side of NE-NW 20 to Nathan High’s son, James High, of Clinton, Michigan, for $1500. The 10-acre strip was sold to Nathan High for $500, giving him a total of 90 acres. James High apparently never moved to Kansas, although he sent two of his sons, Nathan and Hiram, to live with their grandfather.

Because of the failure of James High to pay for the land, it was auctioned off in 1877 and bought for $200 by banker Thomas H. Wills. Due to the failure of the sheriff to record the deed – plus the death of Thomas Wills which resulted in no one realizing the deed hadn’t been recorded – the land reverted to A.M. York. Alexander York transferred the deed to his brother Julius in October 1882. While the matter of his son’s neglect in paying for his land was still in court, Nathan York sold his 90 acres to Isaac Hill, moving to a farm near Liberty.

The 80-acre “Doctor York farm” advertised by Julius York in 1883 didn’t include the 10-acre strip from the NW 20, but it did include a 10-acre strip in the SE 17, part of Nathan’s original purchase, so what started out as two rectangular half sections were now two L-shaped parcels of 80 acres each. The 1881 atlas shows a house on the north side of each parcel.

The 80-acre “Doctor York farm” advertised by Julius York in 1883 didn’t include the 10-acre strip from the NW 20, but it did include a 10-acre strip in the SE 17, part of Nathan’s original purchase, so what started out as two rectangular half sections were now two L-shaped parcels of 80 acres each. The 1881 atlas shows a house on the north side of each parcel.

It is likely that in 1871, Dr. York’s family lived somewhere on the eastern half of the 160 acres that Benton Toal sold to Cheney and High, moving to the west half once the new house was finished in 1872. In her memoir, Mrs. York wrote that neighbors accompanied her to town after her husband’s failure to return home on time; she may have been referring to Nathan and Melinda High.

Today, if you travel from Independence to the Little House on the Prairie Museum via U.S. Highway 75, you’ll cross a corner of the Benton Toal quarter section, between Montgomery County Road 3100 and Montgomery County Road 3600 / Cesna Blvd. A half mile of Montgomery County Road 3625 runs along the northern side of the parcel; there are no homes standing on the Toal / York / High parcels today, and neither the highway or railroad tracks (which predate the road) were there in the 1870s.

Although the Ingalls family had been back in Pepin County, Wisconsin, two years before the murders committed by the notorious Bender family were discovered, the Ingallses have been linked to the story of the Bloody Benders since the 1930s because both Laura Ingalls Wilder and daughter Rose Wilder Lane connected the two families.

Wilder didn’t include the Benders in her handwritten Pioneer Girl memoir, but Rose added the story to subsequent versions as if the disappearance of the Ingallses’ neighbor – and his toddler daughter – happened while they were living on nearby, and that Charles Ingalls had been among the vigilantes hunting down the Bender family after their bodies bodies and others were discovered buried in the Benders’ orchard. When columnist Isabel Paterson mentioned the Bloody Benders in an October 1934 “Turns of the Bookworm” column, Rose sent her a letter, writing that “Kate Bender lived… midway between Independence, Kan., and my grandfather’s log cabin on the Verdigris in Indian territory. My grandfather often stopped there, but though he had a good team, a wagon and (on the return trip) a load of supplies amply justifying his murder, he never could afford to buy a meal from the Benders, but frugally ate by his own campfire… My grandfather was one of the volunteer posse that pursued the fleeing Benders. Darkly, he said little about what happened…” [-Oakland Tribune, January 6, 1935]

The exchange took place during the period that Little House on the Prairie was being readied for publication; the book was released in September 1935 without the Bender story. Laura Ingalls Wilder told the tale in her 1937 Detroit Book Fair speech, however, (published in William Anderson’s A Little House Sampler in its entirety), explaining that it wasn’t a fit story for a children’s book. It’s unclear why Wilder and/or Lane linked their family to the Bender story, as the Bender cabin wasn’t between Pa’s claim and Independence, but in Labette County between Independence and Fort Scott.

Although Wilder didn’t use Dr. York’s name in her Book Fair speech, she did say that “a man came from the east looking for his brother, who was missing,” which is what happened in Dr. York’s case. When he left his farm about seven miles southwest of Independence, he headed to Fort Scott to visit his parents, but never returned home. His body was the first discovered almost two months later.

Little House enthusiasts know that George Newton Longcor and his young daughter, Mary Ann, were also murdered by the Benders. The Longcors were enumerated on the 1870 census in Rutland Township, Montgomery County, Kansas, just after the Ingallses, and Laura and her family were probably still in the area when Mrs. Longcor died just days after Mary Ann’s birth. Although the Ingallses left without buying land on the Osage Diminished Reserve, George Longcor purchased 80 acres, the N-SW 31-33S-15E, a mile east of where the Ingallses are believed to have built their cabin on a school section. Longcor’s in-laws, Mary and Robert Gilmour and their family settled on school land like the Ingallses, and they arranged to purchase 160 acres in January 1872, the N-SE and E-NE 36-33S-14E. That same day, they sold the E-NE to Jesse Mathews for $240.

In July 1872, George Longcor sold his farm to George Mathews (Jesse’s son) for $450, most likely moving in with his in-laws. Longcor decided to take his young daughter east to a sister in late November, and it was on this trip the father and daughter met their end; their bodies were found in the same grave in the Bender orchard. Because the trip was to be a long one, nobody realized the Longcors hadn’t made it to their destination for weeks and weeks, although an abandoned team and blood-stained wagon had been found near Mound City two days after the Longcors left home. News finally reached Robert Gilmour about the abandoned wagon, which he went to investigate in March 1873, identifying the team as that of his son-in-law. As fate would have it, Dr. York was traveling to Fort Scott at the same time, and he identified the wagon as one he had sold to George Longcor. It is believed that Dr. York mentioned the Longcors when he, too, stopped at the Benders, and was murdered.

After the Bender crimes were discovered and George and Mary Ann Longcor were buried on the farm, the Gilmours stayed to settle Longcor’s estate until March 1874, when they moved to Oregon.

Dr. William H. York see also Bloody Benders