Laura’s Sorosis Club speech

Speech about the writing of the early Little House books, given to a service club in Mountain Grove, Missouri.

To my surprise, I have discovered that I have led a very interesting life. – Laura Ingalls Wilder

To my surprise, I have discovered that I have led a very interesting life. – Laura Ingalls Wilder

While working on the manuscript for On the Banks of Plum Creek, Laura Ingalls Wilder gave the following speech at a meeting of the Mountain Grove (Missouri) Sorosis Club.

Sorosis, a professional women’s association, was created in 1868 by Jane Cunningham Croly, because women were usually excluded from membership in many professional clubs. The work of Sorosis was “municipal housekeeping” – applying to municipal problems the same principles of housekeeping that a well-educated woman was expected to practice in the late 19th century.

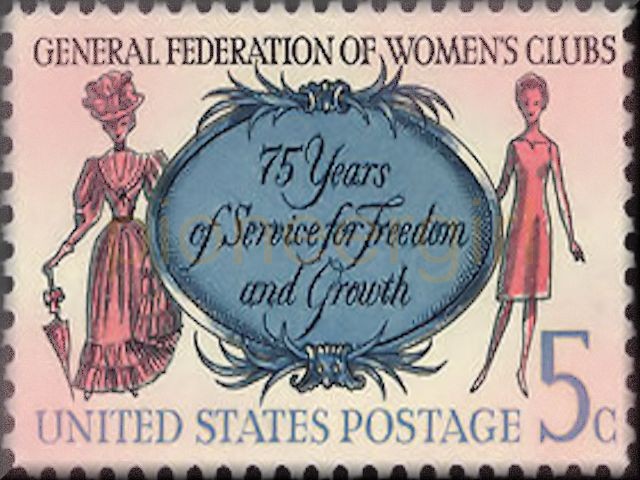

In 1890, delegates from more than sixty women’s clubs were brought together by Sorosis to form the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, whose mission was to help local clubs better organize, while encouraging clubs to work together on lobbying efforts for social reform of health, education, conservation, and government reform.

The Missouri Federation of Women’s Clubs was organized in 1896. There were two clubs in Mountain Grove, the Sorosis Club and the Bay View Reading Club.

The word sorosis comes from the Greek word for aggregation, and from the botanical name for a fruit formed from the ovaries of many flowers merged together. (An example is the pineapple.) It may also have been intended as a term related to sorority, which is derived from the Latin soror, or sister.

Laura’s speech was titled MY WORK, and much of what it included are things that one often hears people mention about Laura, then say that they “heard it somewhere.” Now you can say you read it here!

MY WORK, by Laura Ingalls Wilder.

I hope you will pardon me for making my work the subject of this talk for I had no choice. The children’s story I am writing completely filled my mind.

And again I must ask your indulgence for reading it. Since ten years have passed without my speaking to a crowd, I am some like one of the boys in the recent speaking contest. He said to me, “I was scared plum to death and it was actually pitiful how my knees shook.”

When I began writing children’s stories I had in mind only one book.

For years I had thought that the stories my father once told me, should be passed on to other children. I felt they were too good to be lost.

And so I wrote Little House in the Big Woods.

That book was a labor of love and is really a memorial to my father. A line drawing of an old tintype of father and mother is the first illustration.

I did not expect much from the book but hoped that a few children might enjoy the stories I had loved.

To my surprise it was the choice of the Junior Literary Guild for the year 1932. In addition to this it ran into its seventh edition in its third year and is still going strong.

Immediately after its publication I began getting letters from children, individually and in school classes asking for another book. They wanted to hear more stories. It was the same plea multiplied many times that I used to hear from Rose: “Oh tell me another Mama Bess! Please tell me another story!”

So then I wrote Farmer Boy, a true story of Mr. Wilder’s childhood. This was a few years farther back that my own in a greatly different setting. Little House in the Big Woods was on the frontier of Wisconsin, while the Farmer Boy worked and played in Northern New York state.

Again my mail was full of letters begging for still another book. The children were crying, “Please tell me another story!”

My answer was Little House on the Prairie, being some more adventures of Pa and Ma, Mary, Laura, and Baby Carrie who had lived in the Little House in the Big Woods.

Again the story was true but it happened in a vastly different setting than either of the others. The Little House on the Prairie was on the plains of Indian Territory when Kansas was just that.

Here instead of woods and bears and deer as in the Big Woods, or horses and cows and pigs and school, so many years ago, as in Farmer Boy, were wild Indians and wolves, prairie fire, rivers in flood and U.S. soldiers.

And again I am hearing the old refrain, “Please tell another!” “Where did they go from there?”

After being crowded on from one book into another I have gotten the idea that children like old-fashioned stories. And so I have been working, in my spare time, this winter writing another for them, which will likely be published within the year. It will tell of pioneer times in western Minnesota, of blizzards, of the 1873 [sic] plague of grasshoppers, of Laura’s first school days, of hardships and work and play. With the consent of publishers, I shall call the story On the Banks of Plum Creek.

The writing of these books has been a pleasant experience and they have made me many friends scattered far and wide.

Teachers write me that their classes read Little House in the Big Woods and went on to the next grade but came back into their old room to listen to the reading of Farmer Boy/ and that the next class was as interested as the first had been.

A teacher in Minnesota writes me that Little House in the Big Woods and Farmer Boy are in every third grade in the state.

There is a fascination in writing. The use of words is of itself an interesting study. You will hardly believe the difference the use of one word rather than another will make until you begin to hunt for a word with just the right shade of meaning, just the right color for the picture you are painting with words. Had you thought that words have color?

The only stupid thing about words is the spelling of them.

There is so much one learns in the course of writing, for instance in writing of the grasshopper plague. My childish memory was of very hot weather. In making sure of my facts, I learned that the temperature must be at 68 degrees to 70 degrees for grasshoppers to eat well and it must be above 78 degrees before the swarms will take to the air. If the temperature is below 70 degrees the female grasshopper doesn’t lay well, but above that she may lay 20 or more “settings of eggs.”

In writing Little House on the Prairie I could not remember the name of the Indian chief who saved the whites from massacre. It took weeks of research before I found it. In writing books that will be used in schools such things must be right and the manuscript is submitted to experts before publication.

I have learned in this work that when I went as far back in my memory as I could and left my mind there awhile it would go farther back and still farther, bringing out of the dimness of the past things that were beyond my ordinary remembrance.

I have learned that if the mind is allowed to dwell on a circumstance more and more details will present themselves and the memory becomes much more distinct.

Perhaps you already know all this, but I will venture to say that unless you have worked at it, you do not realize what a storehouse your memory is, nor how your mind can dig among its stores if it is given the job. We should be careful, don’t you think, about the things we give ourselves to remember.

Also, to my surprise, I have discovered that I have led a very interesting life. Perhaps none of us realize how interesting a life is until we begin to look at it from that point of view. Try it! I am sure you will be delighted.

There is still one thing more the writing of these books has shown me.

Running through all the stories, like a golden thread, is the same thought of the values of life. They were courage, self reliance, independence, integrity and helpfulness. Cheerfulness and humor were handmaids to courage.

In the depression following the Civil War my parents, as so many others, lost all their savings in a bank failure. They farmed the rough land on the edge of the Big Woods in Wisconsin. They struggled with the climate and fear of Indians in the Indian Territory. For two years in succession they lost their crops to the grasshoppers on the Banks of Plum Creek. They suffered cold and heat, hard work and privation as did others of their time. When possible they turned the bad into good. If not possible, they endured it. Neither they nor their neighbors owed them a living. They owed that to themselves and in some way they paid the debt. And they found their own way.

Their old fashioned character values are worth as much today as they ever were to help us over the rough places. We need today courage, self reliance and integrity.

When we remember that our hardest times would have been easy times for our forefathers, it should help us to be of good courage, as they were, even if things are not all as we would like them to be.

And now I will say just this… If ever you are becoming a little bored with your life, as it is, try a new line of work as a hobby. You will be surprised what it will do for you.

“My Work”