Great American Desert

A varying area of North America, believed at different times to be uninhabitable by civilized man. The boundaries were constantly changing, and eventually the Great American Desert was proven not to exist at all.

“This country goes three thousand miles west, now. It goes ‘way out beyond Kansas, and beyond the Great American Desert, over mountains bigger than these mountains, and down to the Pacific Ocean. It’s the biggest country in the world…”. – Farmer Boy, Chapter 16, “Independence Day”

“This country goes three thousand miles west, now. It goes ‘way out beyond Kansas, and beyond the Great American Desert, over mountains bigger than these mountains, and down to the Pacific Ocean. It’s the biggest country in the world…”. – Farmer Boy, Chapter 16, “Independence Day”

In Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Farmer Boy, Almanzo Wilder questions a conversation between his father and Mr. Paddock at the 4th of July celebration, during which Father says, “It was axes and plows that made this country.” Father Wilder later explains:

In Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Farmer Boy, Almanzo Wilder questions a conversation between his father and Mr. Paddock at the 4th of July celebration, during which Father says, “It was axes and plows that made this country.” Father Wilder later explains:

“We fought for Independence, son,” Father said. “But all the land our forefathers had was a little strip of country, here between the mountains and the ocean. All the way from here west was Indian country, and Spanish and French country. It was farmers that took all that country and made it America…

“…the Spaniards were soldiers, and high-and-mighty gentlemen that only wanted gold. And the French were fur-traders, wanting to make quick money. And England was busy fighting wars. But we were farmers, son; we wanted land. It was farmers that went over the mountains, and cleared the land, and settled it, and farmed it, and hung onto their farms.

“This country goes three thousand miles west, now. It goes ‘way out beyond Kansas, and beyond the Great American Desert, over mountains bigger than these mountains, and down to the Pacific Ocean. It’s the biggest country in the world, and it was farmers who took all that country and made it America, son. Don’t you ever forget that.” – Farmer Boy, Chapter 16, “Independence Day”

This is the only “Little House” book that mentions the Great American Desert. It’s not in the Farmer Boy manuscript; in fact, Almanzo’s only thought about Independence in the manuscript is that he didn’t remember seeing either the lion that got its tail twisted or the eagle that screamed. He liked the drums and he liked the fifes, but that was about it. A lot of readers probably plow straight through Father Wilder’s speech (added, I suspect, by Rose Wilder Lane) without giving it much thought.

It is but a few years ago that every schoolboy, supposed to possess the rudiments of a knowledge of the geography of the United States, could give the boundaries and a general description of the “Great American Desert.”

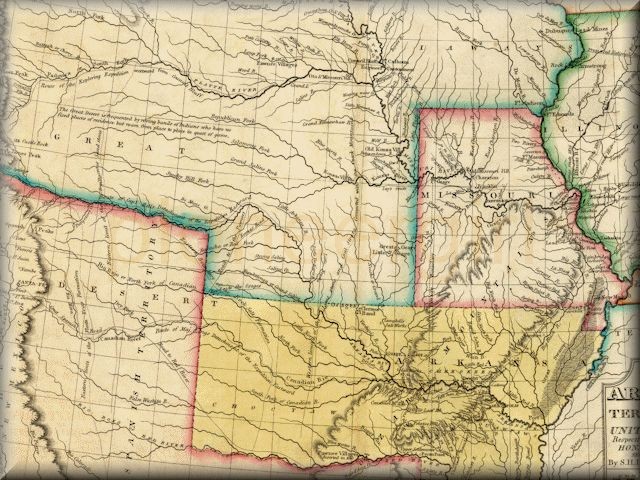

As to the boundary the knowledge seemed to be quite explicit: on the north bounded by the Upper Missouri, on the east by the Lower Missouri and Mississippi, on the south by Texas, and on the west by the Rocky Mountains. The boundaries on the northwest and south remained undisturbed, while on the east civilization, propelled and directed by Yankee enterprise, adopted the motto, “Westward the star of empire takes its way.” Countless throngs of emigrants crossed the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, selecting homes in the rich and fertile territories lying beyond. Each year this tide of emigration, strentghened and increased by the flow from foreign shores, advanced toward the setting sun, slowly but surely narrowing the preconceived limits of the “Great American Desert,” and correspondingly enlarging the limits of civilization. At last the geographical myth was dispelled. It was gradually discerned that the Great Americcan Desert did not exist, that it had no abiding place, but that within its supposed limits, and instead of what had been regarded as a sterile and unfruitful tract of land, incapable of sustaining either man or beast, there existed the fairest and richest portion of the national domain, blessed with a climate pure, bracing, and healthful, while its undeveloped soil rivalled if it did not surpass the most productive portions of the Eastern, Middle, or Southern States. / Discarding the name “Great American Desert,” this immense tract of country, with its eastern boundary moved back by civilization to a distance of nearly three hundred miles west of the Missouri river, is now known as “The Plains”… — General George Armstrong Custer, U.S.A., My Life on the Plains, or, Personal Experiences With Indians (New York: Sheldon & Co., 1876), 7.

At the time of Almanzo’s birth, the Great American Desert was said to be part of the tract between the Rocky Mountains, the Alleghany Mountains, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Great Lakes, specifically the western part of the plain between the Ozarks and the Rocky Mountains..

Early 19th century American explorer, engineer, and inventor, Stephen Long (1784-1864), wrote: “[The Great Plains region] is almost wholly unfit for cultivation, and of course uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence. Although tracts of fertile land considerably extensive are occasionally met with, yet the scarcity of wood and water, almost uniformly prevalent, will prove an insuperable obstacle in the way of settling the country. This region, however, may prove of infinite importance to the United States, inasmuch as it is calculated to serve as a barrier to prevent too great an extension of our population westward, and secure us against the machinations or incursions of an enemy.” (1820)

The Great American Desert first appeared on a map by Long that same year. You can see Long’s map HERE. This will open on a new page.

After several mapping expeditions through land acquired as the Louisiana Purchase, Long declared that a large portion of it was unfit for habitation and was only useful as a “buffer” between the eastern (wooded) part of the country and the lands held by the Spanish, British, and Russians. It was also where hostile Indians lived, tribes Long had run into a time or two during his own exploration.

Long’s label kept settlers from the area for a while, but his misconceptions about the area were soon noted. After all, Long came from New Hampshire, and his idea of what “desirable” land looked like was based on his home state. Note that Father Wilder’s definition of the Great American Desert is slightly broader than Custer’s.

Great American Desert (FB 16)