census taker

census. An official registration of the number of the people, the value of their estates, and other general statistics of a country. — Webster, 1882

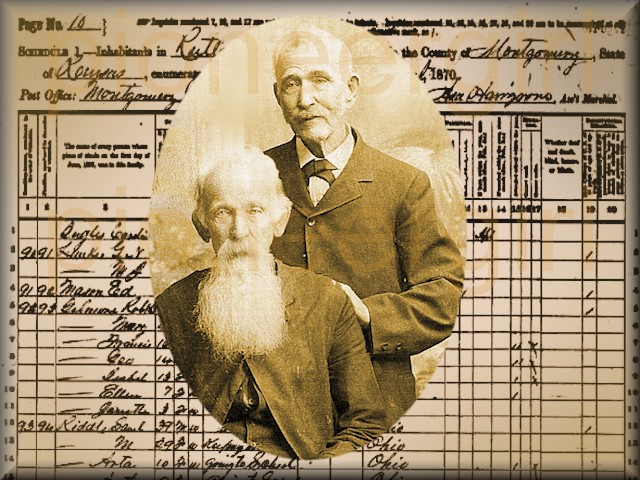

Asa Hairgrove (1826-1881). Montgomery County, Kansas, census taker for 1870 Federal census. He recorded the Ingalls family in Rutland Township on August 13, 1870.

Two years ago Montgomery County was an open plain; the population, as now shows by the census, is 7613 souls. -The Leavenworth Weekly Times, November 3, 1870.

Two years ago Montgomery County was an open plain; the population, as now shows by the census, is 7613 souls. -The Leavenworth Weekly Times, November 3, 1870.

Eileen Charbo’s discovery of the Ingalls family enumerated on the 1870 census in Rutland Township, Montgomery County, Kansas, was key to determining the location of the log cabin built by Charles Ingalls on the Osage Diminished Reserve.

Decades after the publication of Little House on the Prairie, the location of the Ingalls cabin was still unknown. After Harper & Brothers merged with Row, Peterson & Company in 1962 and became Harper & Row, the publisher contemplated removing either the Independence town name and/or any mention of Kansas from Little House on the Prairie unless it could be determined in which state the Ingallses had lived.

Hoping to prove that Laura Ingalls Wilder had been a Kansas author, Eileen Charbo (1911-2012) at Kansas State Historical Society contacted Rose Wilder Lane, who informed her that according to the Ingalls family Bible, “Baby Carrie” had been born in Montgomery County, Kansas, in August 1870, information that Wilder surely knew long before writing her Pioneer Girl memoir and publication of Little House on the Prairie in 1935. Charbo turned to the 1870 Federal Census and found the Ingalls family enumerated in Rutland Township, the 89th dwelling-house of 132 in the 54 square mile township: C.P. Ingles [sic], a carpenter (age 34), wife Caroline (30), and daughters Mary (5), Laura (3), and Caroline (an infant). Portions of census images for the Ingalls family is shown above. Although a primary source document, census information is sometimes incorrect, as noted by the spelling of the Ingalls name.

Hoping to prove that Laura Ingalls Wilder had been a Kansas author, Eileen Charbo (1911-2012) at Kansas State Historical Society contacted Rose Wilder Lane, who informed her that according to the Ingalls family Bible, “Baby Carrie” had been born in Montgomery County, Kansas, in August 1870, information that Wilder surely knew long before writing her Pioneer Girl memoir and publication of Little House on the Prairie in 1935. Charbo turned to the 1870 Federal Census and found the Ingalls family enumerated in Rutland Township, the 89th dwelling-house of 132 in the 54 square mile township: C.P. Ingles [sic], a carpenter (age 34), wife Caroline (30), and daughters Mary (5), Laura (3), and Caroline (an infant). Portions of census images for the Ingalls family is shown above. Although a primary source document, census information is sometimes incorrect, as noted by the spelling of the Ingalls name.

In February 1964, thanks to Charbo’s discovery, a bronze plaque was placed in the Montgomery County Courthouse honoring Laura Ingalls Wilder and proclaiming Rutland Township as the 1870 setting for Little House on the Prairie.

At the urging of her Little House book salesman, Independence, Kansas, bookseller and teacher Margaret Clement (1914-1994) set out to see if she could determine the exact location of the 89th dwelling-place on the 1870 Montgomery County census for Rutland Township, based on the route of the census taker, Asa Hairgrove, who had canvassed the township over two days in August. Knowing that legal claims were first recorded in June 1871 and assuming that many squatters preempted the land they occupied at the time of the census, Clement perused grantee indexes and patent records and was able to pinpoint the claims of fifty-eight 1871-1873 patentees also enumerated on the 1870 Federal Census in Rutland Township.

She found that eight men listed on the census before or after the Charles Ingalls family received patents on land located in six sections in the southeast corner of Rutland township, part of Township 33 South, Range 14 East of the 6th Principal Meridian. According to Clement’s research, there were parcels in two quarter sections in the southeast corner for which patents had not been issued by 1873: Sections 35 and 36. Therefore, she deduced that Charles Ingalls must have built on one of these two sections of land, and it was here she concentrated the remainder of her research.

Clement contacted the owners of the land, William Kurtis (1914-2001) and his wife, Wilma (Horton) Kurtis (1911-2002), as the two quarter sections in question had been in the family since the 1920s. The building of a log cabin and the digging of a well by Charles Ingalls are important stories in Little House on the Prairie. Old-timers couldn’t remember a house or well ever being on Section 35, but according to the Kurtises, there had always been a hand-dug well on the extreme southwest corner of Section 36.What were believed to be foundation stones were soon unearthed near the well. An 1881 atlas showed no dwelling on Section 35, but a house stood on the southwest corner of Section 36. In Clement’s estimation, the Charles Ingalls cabin site had been found.

Quite near them, to the north, the creek bottoms lay below the prairie. Some darker green tree-tops showed, and beyond them bits of the rim of earthen bluffs held up the prairie’s grasses. Far away to the east, a broken line of different greens lay on the prairie, and Pa said that was the river. – Little House on the Prairie, Chapter 5, “The House on the Prairie”

As Margaret Clement wrote, the Kansas site fit Wilder’s description perfectly: “There are bluffs off to the north. Highway 75 cuts through the hidden valley from northeast to southwest. The site is on high prairie south of Walnut Creek… North of Walnut Creek and east of where the Ingalls are thought to have lived there was a known campsite of the Indians.”

The supposed site of the Ingallses’ one-room log cabin on the Kansas prairie has since 1977 been operated as a 501(c)3 non-profit historical museum dedicated to honoring the Ingalls-Wilder heritage. Open annually April through September, Little House on the Prairie Museum is located thirteen miles southwest of Independence, Kansas, on County Road 3000, off Highway 75 to the east. Prairie Days is held the second Saturday each June. The historic site includes an 1872 schoolhouse, the one-room former Post Office from nearby Wayside community, a nineteenth century farmhouse which now houses the Museum’s gift shop, a replica log cabin, as well as a well believed to have been hand-dug by Charles Ingalls.

ASA HAIRGROVE.  Asa H. Hairgrove (1826-1881) was born in Troup County, Georgia, the son of Sarah and William Hairgrove. Opponents of slavery, the Hairgroves were among the earliest non-Indian families in Kansas Territory, settling just west of the Missouri border in Linn County. They fought tirelessly for the Free State movement, and William Hairgrove considered abolitionist John Brown one of his staunchest friends.

Asa H. Hairgrove (1826-1881) was born in Troup County, Georgia, the son of Sarah and William Hairgrove. Opponents of slavery, the Hairgroves were among the earliest non-Indian families in Kansas Territory, settling just west of the Missouri border in Linn County. They fought tirelessly for the Free State movement, and William Hairgrove considered abolitionist John Brown one of his staunchest friends.

There were frequent border skirmishes between Kansas free-state men and their pro-slavery neighbors in Missouri. Charles Hamelton, wealthy Georgia native and slave owner, had been recruited to go to Kansas to aid in the fight for southern rights. He settled in Linn County near the Hairgroves before being driven into Missouri by his opponents. Hamelton then called for volunteers to go with him into the valley of the Marais des Cygnes River “to attend to some devils down there.”

On the morning of May 19, 1858, thirty-two men led by Charles Hamelton rounded up eleven unarmed men at gunpoint, forced them into a deep ravine, and gave the order to fire. Two of the kidnapped men were Asa Hairgrove and his father, William, who were unarmed and had been working in the field when approached by Hamelton’s gang. Six of the men were murdered and five severely injured. Asa was shot in the head (the bullet was never removed from his skull) and his left hand mangled by buckshot, while his father was severely wounded in the arm. The Marais des Cygnes Massacre was considered the last major act of violence of the “Bleeding Kansas” period prior to the outbreak of the Civil War.

Asa Hairgrove was elected Kansas State Auditor in 1862, necessitating a move to Topeka. After being defeated in a run for a second term, he ran a dry-goods store. In the spring of 1869, the Hairgroves were among the rush of settlers to the Osage Diminished Reserve, Asa and his family building within a quarter mile of Richard Dunlap’s trading post at the mouth of Drum Creek. It was in Dunlap’s grove that the infamous Sturges Treaty was signed the previous year.

After being appointed Assistant Marshal, Hairgrove traveled all of Montgomery County as census taker over eleven weeks in the summer of 1870. Rutland Township was the last township he canvassed, with the Charles Ingalls family enumerated on the last day Hairgrove was on the job.

Although not a born farmer, Hairgrove took to it easily, purchasing a quarter section within days of the opening of land sales in July 1871. He ran for Kansas State Auditor again in 1872, but he was defeated; the next year he was elected to the School Board in Independence.

Notoriety came in 1873 when Hairgrove was implicated in a bribery and corruption case involving United States Senator Samuel C. Pomeroy and his accuser, Kansas State Senator and Montgomery County attorney, Alexander M. York. Kansas newspapers weren’t kind to Asa Hairgrove, and he sold his Montgomery County land and moved with his family to Colorado, where he died in 1881.

THE CENSUS TAKER’S ROUTE IN 1870. Federal and Kansas state censuses, tract books and patent records, plus period maps, atlases, and other primary source documents are now online, allowing Clement’s census-route project to be reconstructed. Ninety-two Montgomery County patentees who also were enumerated on the 1870 census were easily located, with Asa Hairgrove’s route shown as more than a dozen meandering lines that marked from two to thirteen households enumerated consecutively, with others pinpointed without reference to their nearest neighbor. There is no way to know if Hairgrove visited each household or if he might have obtained information pertaining to one family while canvassing another (as Clement speculated based on the misspelling of the Ingalls name as Ingles). However, it is important to note that Clement based her location of the Ingallses’ home site on the order of the census taker, and it was a requirement of the census enumerator to record each dwelling house in number as it was visited.

Ten days after Carrie Ingalls’ birth, Hairgrove began his second day of canvassing in Section 17, Township 33 South, Range 14 East of the 6th Principal Meridian, near where the Atlanta Post Office was established in 1870; it was changed to Rutland Post Office four years later. The eight families listed before or after the Ingallses on the 1870 census indeed settled and purchased land in southeast Rutland Township, with one enumerated family to the east in Township 33, Range 15. Clement hadn’t pointed out that the census-taker’s route occasionally crossed township lines.

In census order, families (and the land they purchased) immediately surrounding the Ingallses included:

85. Joseph L. James: NW-NW 25 & SW-SW 26 & SE-SE 27 & NE-NE 35-33-14

86. Alexander K. Johnson: SE-SW 26 & SW-SE 26 & NW-NE 35 & NE-NW 35-33-14

87. John R. Rowles: S-NE 34 & N-SE 34-33-14

88. Bennet Tann: E-NE 35-33-14 & W-NW 36-33-14

89. Charles P. Ingalls: SW 36-33-14, no claim filed

90. George N. Longcor: N-SW 31-33-15

91. Edmund Mason: E-NW 36 & W-NE 36-33-14

92. Robert B. Gilmour: E-NE 36-33-14

93. Samuel Riddle: NE 25-33-14

In order to construct my own census route map, I pieced together township map images from the 1881 atlas and marked the boundary of claims patented in the 1870s. Both Charbo and Clement failed to address the fact that Sections 16 and 36 were not part of the Diminished Reserve lands sold, being set aside as school sections sold by the State of Kansas as stipulated in the 1870 treaty with the Osage Indians. The 1870 census recorded the order in which dwelling houses and families were enumerated, the name of every person living in said abode on the first day of June 1870, their age as of last birthday, sex, race, occupation or profession, value of personal estate, place of birth, and other statistics. There was a column for value of real estate (land) owned, but as the land belonged to the Osage Indians, the squatters had no right to said land.

Click HERE to learn about the some of the treaties with the Osage Indians negotiated prior to the Ingallses’ arrival in Indian Territory or during the Little House on the Prairie years.

Click HERE to see my map showing a portion of Hairgrove’s route and to learn about the steps Charles Ingalls might have taken had he remained in Kansas and purchased Kansas school land and/or Diminished Reserve land sold by the federal government.

census